To continue fromwhere we left off in the previous post (you may want to go back and read that

if you haven’t) let’s look at another evolutionary arguments for the importance

of our microbiome. Bacteria have been colonising humans since we first

existed. Human eating habits have changed a lot within a very short period.

Throughout much of our evolutionary time we have eaten a diet ripe in bacteria

– meat caught and slaughtered outside, vegetables grown naturally in fields and

so on. However, within recent times our food production (and consumption) has

changed. Processed foods have become increasingly common, and these are largely

sterile. Additionally, antibiotics are heavily used in the animal farming industry;

reducing the amount of bacteria we receive from our food. Some claim that this

may be disrupting our microbiome, as we are not getting the same level and

diversity of bacteria. Furthermore, this disruption caused by out eating habits may be

playing a role in the development of obesity in the Western world. Obviously

the diet itself plays a major role in obesity, but the microbiome may also

contribute. Consider the fact that if we have a gut full of bacterial cells all

needing energy, they are going to take what they need from the food we ingest,

before we absorb it for ourselves. If we have less microbes, in the gut, and

less coming in with our food, then less energy will be taken out of the system,

potentially allowing more to enter into our bodies; this excess of energy may

well be play a significant role in obesity.

To continue fromwhere we left off in the previous post (you may want to go back and read that

if you haven’t) let’s look at another evolutionary arguments for the importance

of our microbiome. Bacteria have been colonising humans since we first

existed. Human eating habits have changed a lot within a very short period.

Throughout much of our evolutionary time we have eaten a diet ripe in bacteria

– meat caught and slaughtered outside, vegetables grown naturally in fields and

so on. However, within recent times our food production (and consumption) has

changed. Processed foods have become increasingly common, and these are largely

sterile. Additionally, antibiotics are heavily used in the animal farming industry;

reducing the amount of bacteria we receive from our food. Some claim that this

may be disrupting our microbiome, as we are not getting the same level and

diversity of bacteria. Furthermore, this disruption caused by out eating habits may be

playing a role in the development of obesity in the Western world. Obviously

the diet itself plays a major role in obesity, but the microbiome may also

contribute. Consider the fact that if we have a gut full of bacterial cells all

needing energy, they are going to take what they need from the food we ingest,

before we absorb it for ourselves. If we have less microbes, in the gut, and

less coming in with our food, then less energy will be taken out of the system,

potentially allowing more to enter into our bodies; this excess of energy may

well be play a significant role in obesity.

The use of

antibiotics by farmers also argues for a role of the microbiome in obesity. The

reason antibiotics are used by farmers is from the observation that this practice

caused a gain of weight in the animals. For a long time this was not

understood, but now with the evidence emerging from humans and other animal

studies it appears that this affect could be down to the depletion of the microbiome

caused by the antibiotics. A further example comes from studies in mice which have shown that transplanting the microbiome from an obese mouse into a thin

mouse leads to weight gain. The reverse has also been seen. If this holds true

in humans then targeting the microbiome may be a feasible way to tackle the obesity

epidemic of the Western world.

Changing tack slightly, as you may be

aware, antibiotics have been overused for a long time, leading to major worries

over antibiotic resistance and reversion to a pre-antibiotic era. This is a huge

worry, however the overuse of antibiotics may have additional consequences that

we are only just starting to realise. It has been found that people in the

Western world are now largely devoid of the bacterium Helicobacter pylori,

which is common in the guts of people in areas of the world less rife in the use of

antibiotics. Removal of H. pylori isn't a bad thing per se; this bacterium is

known to cause peptic ulcers and stomach cancer. However, the importance of H.

pylori is a nice shade of grey and we have only noticed the beneficial effects

now it’s gone.

H. pylori plays

an important role in controlling stomach acid production and people devoid of

it are at a much higher risk of developing acid reflux. Acid reflux can lead to

a condition known as Barrett's oesophagus and eventually certain forms of

oesophageal cancer if left untreated. Coincidently with the loss of H. pylori

from the gut microbiome in the West, rates of oesophageal cancer have soared. Furthermore,

H. pylori is able to control inflammatory responses. This control may be

important for regulating allergies, which are caused by an inappropriate

inflammatory response against something harmless (such as pollen).

Similarly to the rates of oesophageal cancer, it is well documented that there

are an increasing number of people with allergies in the Western world. Finally, H. pylori may also be important in obesity, as it is known to regulate the

hormone ghrelin, which regulates our appetite. All of this has led to some suggestions

that we should inoculate babies with H. pylori. Obviously this raises

ethical issues because of the potential for peptic ulcers and stomach cancer,

but these are largely only seen later in life. The current idea is that we should

inoculate at a young age and then give antibiotics to kill the bacteria later in

life, getting the best of both worlds.

A mentioned, H.

pylori may be playing a role in the inflammatory response and development of

allergies. However, the link between resident bacteria and the immune system

doesn’t end there. It appears that our whole microbiome is essential for the

development of a proper immune system that doesn't attack the wrong things. Without

the bacteria in our guts it is thought that the immune system may become hypersensitive

and attack everything, leading to allergies.

|

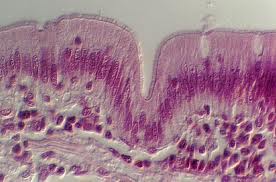

| Histological section of intestine lining |

Sticking with

the immune system, many chronic diseases have inflammation as an underlying

cause. Inflammation is an essential part of our immune response, but is only

beneficial if it is transient; sustained inflammation leads to damage around

the body. It has been found that Bifidobacteria and Lactobacilus species in the

gut are essential for maintenance of the epithelial lining in this organ (the

cells that make up the walls of our gut). A proper epithelial lining plays an

essential role in the passage of nutrients out of our digestive system into our

blood. The lining needs to be ‘selectively permeable’ so that only certain,

useful, things get through. If the lining becomes ‘leaky’, then unwanted

molecules can get through such as bacteria and their toxins or whole protein

molecules (instead of just the amino acids we normally absorb from the gut),

all of which could trigger an inappropriate immune response. Since

Bifidobacteria and Lactobacilus are needed for maintenance of the epithelial

lining, any disruption to these bacteria will have an impact on the integrity

of the barrier. Indeed, it has been shown that mice fed on a "junk

food" diet have a disruption of these bacteria and develop a ‘leaky

epithelia’. This caused a low level systemic inflammatory response, which

eventually causes metabolic diseases. It is therefore highly possible that many

disease with inflammation as an underlying cause could originate from issues

with out internal bacterial species.

The final thing

I'd like to discuss is that the notion of thinking with your gut may hold more

truth than you know. It has been found that microbes in the gut are important

for the generation of neurotransmitter molecules such as serotonin and thus may

be playing an important role in regulating mood. Furthermore, there is evidence

suggesting a link between the gut microbiome and the hypothalamic-pituitary

axis (HPA), a region of the brain that shows disruption during clinical

depressive episodes. Mice bred to have no microbiome show an enhanced stress

response that can be curtailed by the introduction of a microbiome - this

response, to a large extent, is generated from the HPA. Additionally, it been

shown in mice that if the microbiome of adventurous mice is transplanted into

the guts of timid mice they lose their inhibitions and become more adventurous,

further supporting the notion that our gut bacteria may be influencing our

brains.

The final thing

I'd like to discuss is that the notion of thinking with your gut may hold more

truth than you know. It has been found that microbes in the gut are important

for the generation of neurotransmitter molecules such as serotonin and thus may

be playing an important role in regulating mood. Furthermore, there is evidence

suggesting a link between the gut microbiome and the hypothalamic-pituitary

axis (HPA), a region of the brain that shows disruption during clinical

depressive episodes. Mice bred to have no microbiome show an enhanced stress

response that can be curtailed by the introduction of a microbiome - this

response, to a large extent, is generated from the HPA. Additionally, it been

shown in mice that if the microbiome of adventurous mice is transplanted into

the guts of timid mice they lose their inhibitions and become more adventurous,

further supporting the notion that our gut bacteria may be influencing our

brains.